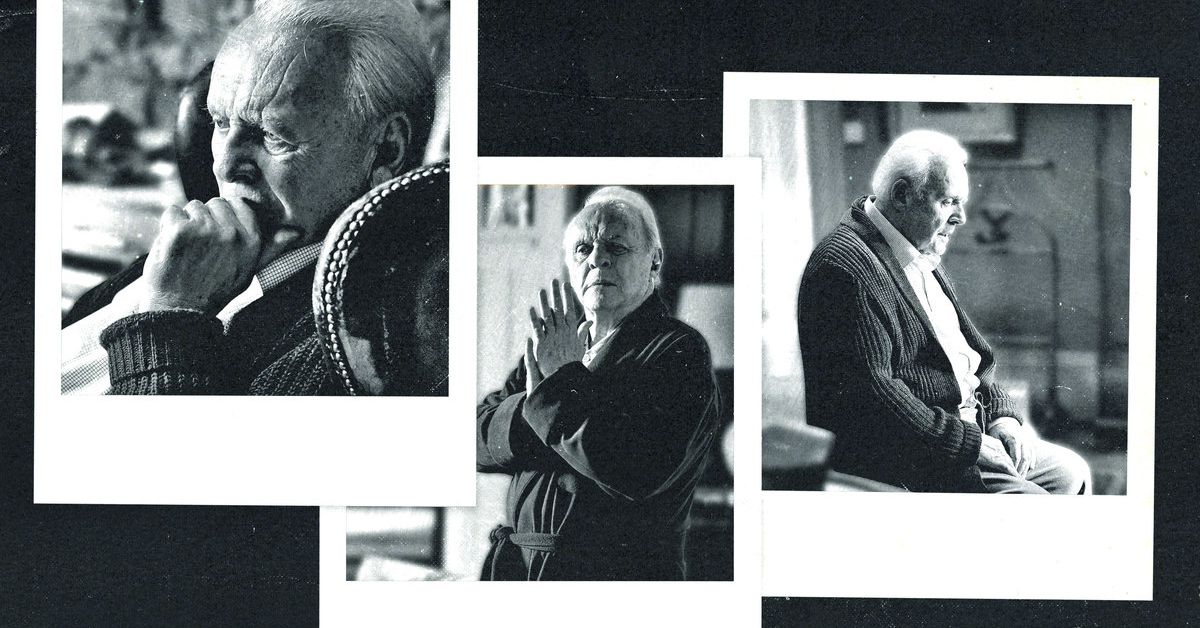

Netflix/ Ringer Illustration

In Florian Zeller’s elegiac’ The Father, ’ Hopkins demonstrates one of the most significant concerts in his storied profession, playing a character grappling with his own mortality

In The Father, Anthony Hopkins dallies Anthony, a soul who’s trying to figure out how “peoples lives” fits together. He’s become the missing piece in his own private jigsaw baffle. Stalking around his comfortable flat in London, the 80 -something widower tells anybody who’ll listen–mostly his adult daughter, Anne( Olivia Colman ), who drops in and out on regular sees that evaluation her nerves–that he’s fine, and that his sentiment is like a steel trap. But there’s rust around the edges.

Anthony forgets specifies and times and loses move of epoch; he hides valuables in a secret spot and later thinks that they’ve been lost or stolen; he’s plagued by hallucinations of strangers and loved ones, living and dead. The utterance “dementia” is never spoken aloud, but it hangs there in the accommodation like a specter. “I can look after myself, ” Anthony holds. It’s as if he’s trying to convince himself. Sometimes it operates, sometimes it doesn’t. The surest indicate that Anthony is scared is that he’s put on such a brave face.

Recent Comments