Elizabeth Schwaiger, “Flooded Springs”( 2019 ), oil, acrylic, ink on canvas, 39 x 48 inches

Elizabeth Schwaiger, “Flooded Springs”( 2019 ), oil, acrylic, ink on canvas, 39 x 48 inches

It basically goes without saying that most people prefer to view visual artwork in person rather than online. Virtual exhibitions have been necessary proxies for firsthand knowledge during the time of social distancing, but they can’t amply convey sensorial characters such as texture, flake, and sun. What’s more, looking at art in person is about more than only aesthetic knowledge. It can also be an occasion to spend time with friends, dialogue with gallerists, schmooze with relationships and strangers at an opening, get some lighting activity, inspect a neighborhood or metropoli, or, for the influencers among us, move some artistry selfies. The consider event was bound to feel abated when shunted entirely online.

Dealing with the estrangement abide of secondhand acquaintance may be a new phenomenon for the art industry but it has long been a core concern of eco- and climate-themed art. Because climate change arises across gigantic tracts of space and season, an example of what eco-philosopher Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects, ” humen only experience it in glancing, piecemeal practices. Instead, we know climate change predominantly through arbitration: a graph outlining atmospheric carbon dioxide heights over term; a bird’s-eye-view map of arctic frost loss; before and after photographs of a withdraw glacier. One style eco-art and its cognates have addressed this epistemic disjunct is to render it evident, as when Agnes Denes planted her loathsome “Wheatfield — A Confrontation”( 1982) next to the lower Manhattan skyline.

Whatever their efficacy, such aesthetic gestures foster eco-consciousness in a unique, personified lane. They grant imaginative kind to complex, abstract-seeming phenomena — the food chain; commodities markets; ecological consume — and, in so doing, can utter those phenomena easier to fathom, more tangible. Most artistic media are well-suited for this ontological alchemy but depend on physical vicinity to achieve their full impacts. It’s the difference between accompanying a photograph of a cover and hearing the make-up in person, the difference between seeing an image of a wheat domain and feeling wheat stems crunch underfoot as imperfections swirl around you in the earth-scented air. What happens, then, to the viewer experience of eco-art when shifted online and what might it suggest about the specific characteristics of the online hall suffer?

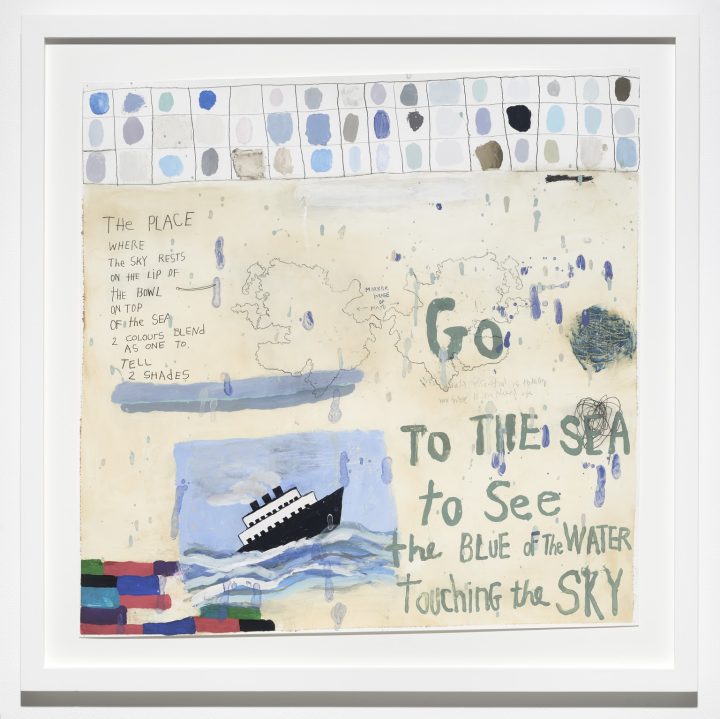

Squeak Carnwath, “Go to the Sea”( 2018 ), gouache and graphite on polypropylene, 29.3 x 29.3 inches

Squeak Carnwath, “Go to the Sea”( 2018 ), gouache and graphite on polypropylene, 29.3 x 29.3 inches

Absence realise the heart change fonder

The directive “Go/ To THE SEA, ” written in teal blue gouache, enjoins the textbook, “to See/ the BLuE oF The WATER/ hit the SKY.” This poetic instruction in Squeak Carnwath’s mournful painting “Go to the Sea”( 2018) performs as an apt entry into Jane Lombard Gallery’s attractive online exhibit In Celebration of the Natural World, organized in response to New York City’s COVID-1 9 stay-at-home line-ups. Same to how the considering room provides as a digital substitute for the impassable hall, “Go to the Sea” gestures toward an experience that can’t occur within the decorate itself.

Carnwath is well aware of painting’s limitations and possibilities. Instead of trying to provide a conceivable mimetic substitute for the juxtaposition of spray and sky off-colors, she incorporates into the work one of her signature color grids — associative daubs of a liberate color pedigree, in this case blue — to highlight the difference between a painter’s palette and hue as it exists beyond the enclose. An illustrative memorandum incorporated within the grid of light-green and brown daubs atop her decorating “How Many Greens”( 2018) also emphasizes the disjunct between art and life: “from memory of direct see( of principally growing things& plant life ). ”

Just as Carnwath’s covers cuddle their own artifice rather than feign verisimilitude, online exhibitions are better off focusing on the medium’s persuasiveness than trying to replicate the gallery experience. In Celebration of the Natural environment has the same features as most commercial galleries’ online ending apartments: portraits of individual artworks, each with a button for obtain investigations, along with snippets of explanatory textbook. If the observer isn’t familiar with the effort, as was the case for me with Elizabeth Schwaiger’s beguiling oil painting of hallucinatory avalanches, it is hard to know what the secondhand experience might occlude.

Still, deterring things simple seems preferable to trying to simulated the gallery experience in virtual infinite. For example, Artificial Ecologies, an online show curated by Isabel Beavers for CultureHub’s Re-Fest, showcases office by four eco-artists( Richelle Gribble, Maru Garcia, Julian Stein, and Beavers herself) in a pixelated 3D environment whose save, blocky architecture remembers first-person 1990 s computer games such as Myst. The exhibition’s soundscapes were impelling but its spatial environment was difficult to navigate and visually reductive. When I followed the link to Julian Stein’s craftsman website to watch an embedded Vimeo of his strange generative tone station, “the wind repeats itself: off-color grama”( 2017 ), the return to a grassland interface felt welcome.

All that’s solid

Artist Julia Christensen’s thought of “upgrade culture” — the idea that new digital technologies need always to oust old-time ones — volunteers a big-picture perspective on questions of replaceability in both art and life. Her excellent artist book from Dancing Foxes Press, Upgrade Available, as well as an eponymous online expo at ArtCenter College of Design, explore the material consequences of upgrade culture’s consumerist logic. Christensen’s project is the synthesis of nearly a decade of applied artistic investigate, including visits to e-waste processing seeds in India, a residency in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Art+ Technology Lab, an ongoing collaboration with scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab( JPL ), and a self-inventory of her private archive of house idols and videos.

How gatherings assimilate the results of such a heterogeneous programme depends in no small-scale division on its method and medium of proposal. ArtCenter’s online exhibition — a brief medley of portrait and text for each of the project’s major components — wisely doesn’t pretend it can do much more than add a sampler menu for the adjourned hall exhibition. The work, on the other hand, showcases the project in its full magnitude and breadth. It includes portraits, thematically coordinated essays by, and conversations with Christensen( her conversation about e-waste with Indian craftsman Ravi Agarwal is particularly eye-opening ). It would be difficult to exaggerate how frequently Dancing Foxes Press develops those kinds of grandiose skill job into an appealing, context-rich book; its catalogue , now almost a decade age-old, rectifies a high standard for what an artist notebook can be and do.

It’s fitting that Upgrade Available works well as a journal, considering its uneases about technological obsolescence. It labours so well in part because Christensen is an insightful scribe — with a penchant for neologistic conceptions such as “upgrade culture, ” “technology time, ” and “institution time” — and in part because the project itself, brimming with narrative and conceptual intricacies, is perfectly suited to written discourse. The diary format left me especially curious to experience the artworks in person. While a photographic series such as Technology Time( 2011 -ongoing ), which outlines forlorn slews of outdated e-waste, changes successfully to book and website idols, a sculptural facility such as Burnouts( 2013) — juttings of supernatural constellations no longer perceptible due to light pollution, which call abandoned iPhones as the installation’s simply light source — seems dependent on firsthand witnes experience.

Julia Christensen, antenna tree framework( Mt. Wilson ), digital photo, facets variable, from” Tree of Life”( 2019 -ongoing)

Julia Christensen, antenna tree framework( Mt. Wilson ), digital photo, facets variable, from” Tree of Life”( 2019 -ongoing)

Dynamics of attendance and omission, interval and closenes, are essential in Upgrade Available’s as-yet-unbuilt capstone assignment, Tree of Life( 2019 -ongoing ). In an effort to think far beyond the time horizon of scheduled obsolescence, Christensen and her NASA JPL collaborators are developing a satellite that will orbit earth for 200 times and communicate with a tree whose stalk and limbs are outfitted with donut-shaped antennae that loosely resemble echoes hooped around resound toss pegs. Data about both the tree’s and the satellite’s environmental health will be translated into audible sonic frequencies that can be transmitted via radio to comprise a symbolic “2 00 -year duet.” Like British composer Jem Finer’s 1,000 -year-long song, “Longplayer”( 2000 -ongoing ), Christensen’s Tree of Life is designed to outdo the spatial and temporal obliges of individual know. The question is whether an artwork that is itself a hyperobject is best suited to address the epistemic disjunct intrinsic to the human experience of other hyperobjects.

If a tree comes in the forest

Meteorological Mobilities, an online exhibition curated by Marianna Tsionki for what was planned as a gallery exhibition at New York City’s apexart, contemplates this issue by bringing it back down to earth. The exhibition’s four artworks illustrate the human displacement that is already occurring in different places around the globe as a result of climate change. This humbly potent see advocates not only aesthetic approaches for addressing eco-alienation but also curatorial programmes for deal with the alienation viewers suffer with online showcases. In special, the on-line version of apexart’s explanatory brochure equips contextual ballast without strain the viewer’s courtesy span.

MAP Office, Learning from the Gypsies: Ghost Island( 2019 ), digital video, 40 min( still)

MAP Office, Learning from the Gypsies: Ghost Island( 2019 ), digital video, 40 min( still)

Another thing that fixes Meteorological Mobilities effective is that three of its four pieces are videos, an artistic medium that works particularly well in the online environment. For example, MAP Office’s imaginary 40 -minute film Learning from the Gypsy: Ghost Island( 2019) portrays, with almost no dialogue or drastic conflict, the quotidian fisherman’s life for Gung, a member of the southeast Asian Urak Lawoi’ tribe. Gung lives in a “Ghost Island, ” a waterlogged latticework architectural shanty that MAP Office’s artistic duo of Laurent Gutierrez and Valerie Portefaix have installed at exhibition websites around Asia. The differ between the structure’s impracticality as shelter( it’s absolutely porous to the elements) and Gung’s survivalist routine times up the benefits of MAP’s delicately fictionalized approaching. The film, along with its accompanying mock-touristic postcard serial( “Greetings From Ghost Island, Thailand! ” ), never pretends to be pure anthropology and, as a result, achieves surprising keennes and watchability.

Kivalina: The Coming Storm( 2014) manages to be even slower speeded and less action-filled than Ghost Island yet just as engaging. Produced by leading cadres of artists for research projects, Modeling Kivalina, begun under the umbrella of Forensic Architecture( Andrea Bagnato, Daniel Fernandez Pascual, Helene Kazan, Hannah Meszaros Martin, and Alon Schwabe ), the non-fictional video recounts the plight of the Inupiat village of Kivalina, which is situated on a impediment island along Alaska’s northwest coast and imperiled by rising sea level. As occupants narrate in voiceovers their tribe’s embattled past( in 1905 the Bureau of Indian Affairs pressured the Inupiaq to settle in Kivalina ), the camera remains fixed on a vantage of the ocean’s horizon as seen from the shore. No humen, or human-made things, appear on screen for the video’s 35 – minute duration, precisely brandishes sipping against the coast, at first calmly, then with increased agitation.

It’s no coincidence that these two videos from Meteorological Mobilities have been the most powerful visual artistry I’ve knew since museums and galleries went online in March. Both use aesthetic understatement to convey a sense of how sees can be physically unplugged from, yet still somehow implicated in, a phenomenon much larger than themselves. There’s a real sense — with importances our categories has only just begun to endure — in which existentially threatening hyperobjects such as climate change and the coronavirus pandemic feel absurd to the humans who undergo them. Certainly, such objects call into question what it even means to speak of encountering them first- or secondhand. Online exhibitions of eco-art can’t definitively answer that question but they can allow witness to feel the extent to which they’re alienated from a crucial aspect of their own experience.

In Celebration of the Natural World is currently online at Jane Lombard Gallery.

Artificial Ecologies continues online at Culture Hub’s Re-Fest through June 30.

Julia Christensen: Upgrade Availableis currently online at ArtCenter.

Upgrade Available by Julia Christensen is published by Dancing Foxes Press and is available online and from indie booksellers.

Meteorological Mobilitie is currently online at apexart.

Read more: hyperallergic.com

Recent Comments