Found footage horror movies represent the best and worst sides of the genre. On one hand, they are indicative of the low-budget ingenuity that has inspired the creative filmmaking of horror classics. On the other hand, they embody the repetitive storytelling and tired tropes that critics have targeted the horror genre for embracing. Since the landmark The Blair Witch Project, though, changes in technology and media have morphed the subgenre into different forms, proving that found footage is at least more than a static fad.

The found footage technique has crossed over into various genres over the years, but horror filmmakers have utilized it the most. Watching what feels like a piece of raw, uncovered footage can be deeply unsettling, blurring the barrier between fact and fiction by evoking a mysterious sense that the viewer is witnessing something perverse and forbidden. In addition, the format lends itself to lower budgets that horror directors often embrace in the scene to film cheap, grainy, DIY masterpieces.

Related: Why The Blair Witch Project’s SyFy Mockumentary Was Better Than The Sequels

For all their faults and criticisms, found footage films remain a fascinating way to look at how contemporary audiences consume media. The subgenre started off as a response to the Internet, reality television, and easier accessibility to home recording devices, and rose in popularity as viral videos become more commonplace. However, the demand for these films dwindled after the turn of the 2010s as the style became worn-out. Still, though, as technology continues to rapidly evolve and filmmakers discover new visual modes of storytelling, the thrill of the found footage horror movie may yet survive.

Before The Blair Witch Project, there was Cannibal Holocaust, which was released in 1980 and is often cited as the first found footage movie. The film, which follows a documentary crew’s journey into the depths of the Amazon rainforest, was and is still met with controversy due to its graphic violence and real, on-screen killings of animals. The result was so viscerally violent that director Ruggero Deodato was arrested in his native Italy on obscenity charges.

Cannibal Holocaust has more in common with ’70s exploitation than it does modern found footage, but it did pave the way for the technique with its cheap, grimy aesthetic that disturbingly resembles a snuff film. Deodato also created a myth behind his film, making it seem as if the footage might be real by convincing his actors to disappear from the public eye after shooting. It wasn’t until the cast appeared in court that the director was cleared of possible murder charges, but the power of sensationalized marketing would have a profound impact on found footage horror films decades later.

The Blair Witch Project arrived in a sweet spot in cultural history. Video recording and editing technology were becoming more accessible to the average person, but mass video-sharing had not become a staple yet. The Internet was still fairly new and exciting, right in the middle of the “dot-com bubble” with ample forums and blogs for online discussion but still far from the information hub it is today. Reality television was on the rise, and there was just enough amateur camcorder footage in circulation to convince audiences that this new horror movie might very well be real.

Related: Blair Witch Project Had A Negative Impact On Its Maryland Town

To be fair, a lesser-known movie called The Last Broadcast predated Blair Witch by a year, but the two were in production at the same time. Both movies took advantage of the zeitgeist and relied on consumer-level recording equipment to give the impression of a “true story”. While The Last Broadcast utilized a “mockumentary” approach using faux interviews and documentary editing techniques, The Blair Witch Project came across as more literal “found footage”, as if someone had uncovered the camcorder and viewed the raw, unedited material.

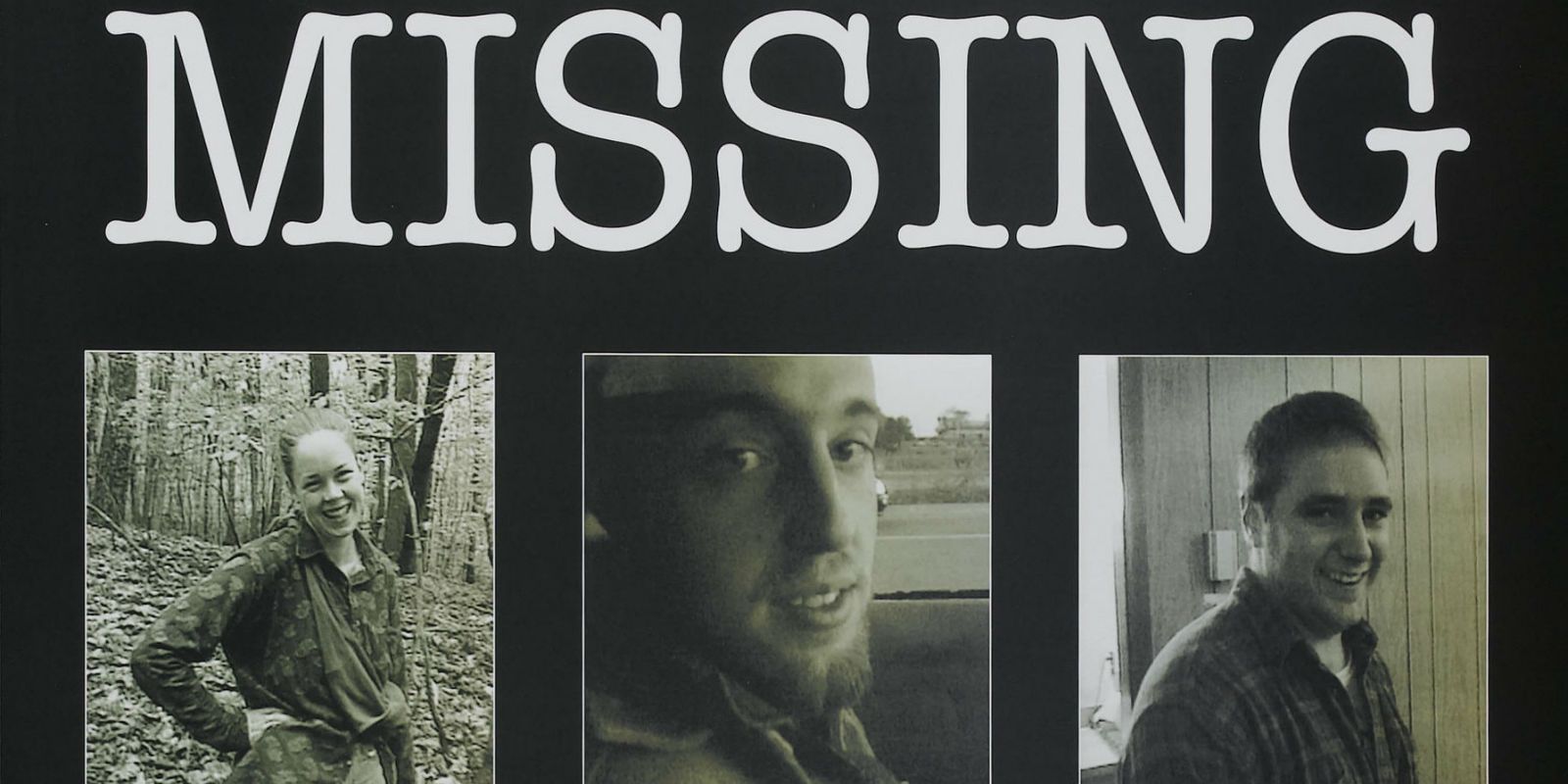

Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez used Hi8 analog videotapes and 16mm film, which had traditionally been used in amateur home videos and documentary reels, to both enhance the feeling of watching home camcorder footage and to keep the budget down. The film is perhaps most remembered for its elaborate marketing campaign, which included a website detailing a police investigation of the case and a missing persons poster. The Blair Witch Project managed to make $250 million off of a $60,000 budget, an impressive feat aided by the public’s growing fascination with candidly shot amateur videos and the power of the Internet.

For almost a decade, the success of The Blair Witch Project was seemingly a one-time gimmick. As the Internet rapidly expanded to a part of daily life, it seemed as if nothing could capture the same mythical dread. Meanwhile, in 2005, YouTube started to radically alter the concept of video sharing and viral content to its current form. In this way, a found footage comeback was inevitable, as long as it could pierce through the increasingly crowded pool of viral content.

Cloverfield and Paranormal Activity weren’t the first films of their type to emerge at this time, but they were certainly the most responsible for launching the found footage craze that engulfed pop culture at the turn of the decade. Entries like the faux snuff mockumentary The Poughkeepsie Tapes and George A. Romero’s Diary of the Dead failed to find a mainstream audience, but mysterious viral marketing and critical acclaim helped Cloverfield reap a comfortable profit. Then, around Halloween of 2009, came the mega-hit Paranormal Activity, which had already been building up rumors about people leaving the theater out of fright since its festival debut two years earlier.

Related: Why Noroi: The Curse Is Being Called The Scariest Found Footage Movie Ever

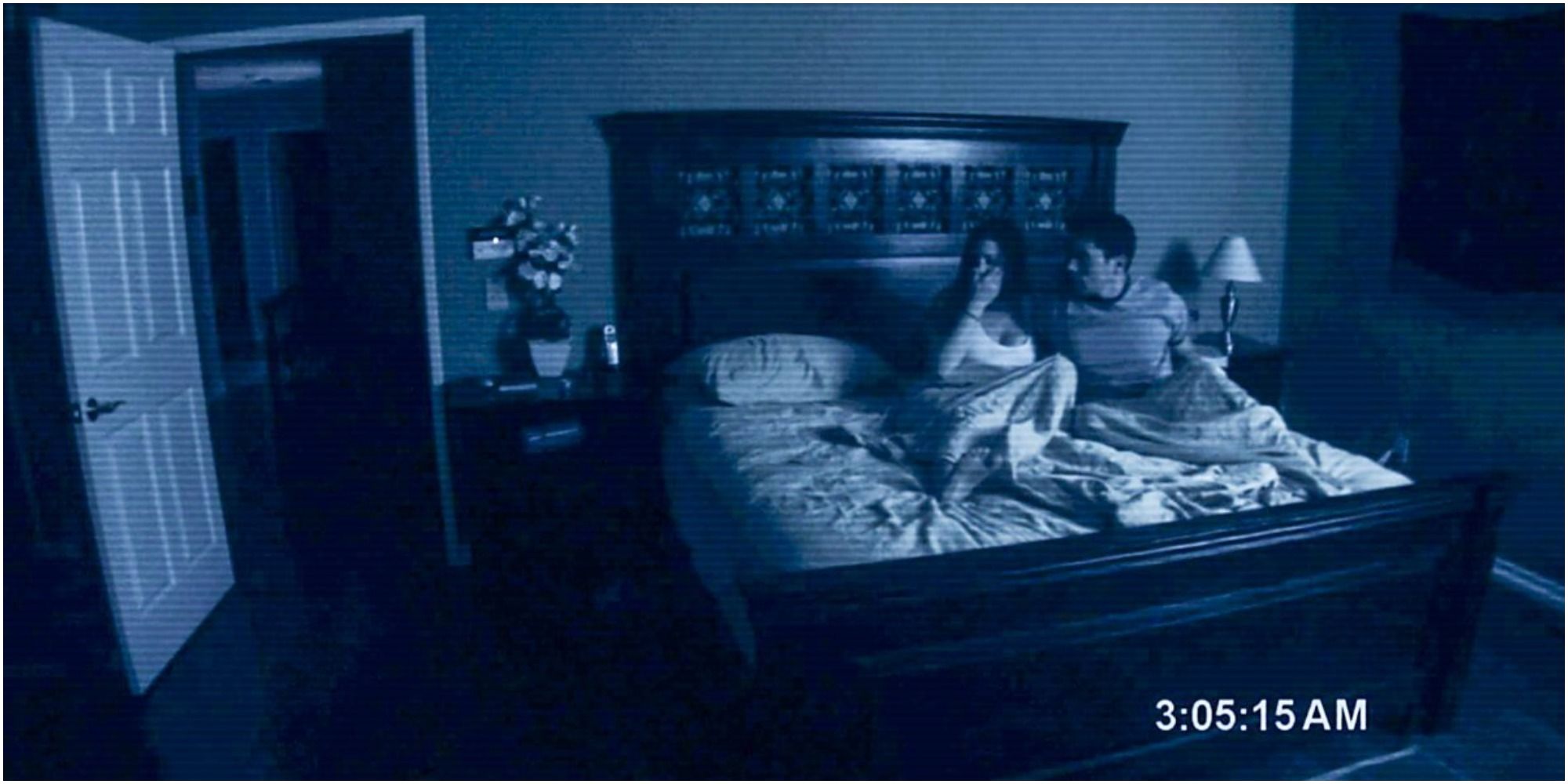

Paranormal Activity was perhaps the first and last film to capture at least an ounce of Blair Witch’s is-it-real-or-is-it-not sensation, changing the visual storytelling device from handheld camcorder footage to more intrusive-feeling home security cameras. The film was a roaring success, cited as the most profitable film at the time when box office returns are compared to budget. A renewed interest in the found footage style exploded as the sub-genre impacted cinema across all genres, such as in the superhero sci-fi Chronicle and the teen comedy Project X. However, the boom turned into a glut as the mystery and thrill of found footage started to wear off.

There were legitimately creative endeavors into the limits of found footage filmmaking, from the creepily voyeuristic to the compelling replication of contemporary media. The 2007 Spanish film REC, which followed a news crew instead of a group of amateurs, developed a cult following overseas and led to an American remake called Quarantine in 2008. District 9 received praise at the Academy Awards for the way it poignantly and relevantly presented fictional news footage as a narrative device in 2009. At the same time, duds like The Chernobyl Diaries and Apollo 18 proved that these types of movies were perhaps over-relying on style instead of story.

V/H/S arrived towards the end of the found footage boom in 2012 and, in many ways, is indicative of the best and worst excesses of the subgenre. The horror anthology experimented with different types of found footage styles to varying levels of success, but it was arguably a segment filmed entirely through Skype video calls entitled “The Sick Thing That Happened to Emily When She Was Younger” that was a harbinger of what was to come. Phone footage and news reels and already taken the place of camcorder technology in both cinema and the real world, but video chat presented a new opportunity for found footage filmmaking.

Unfriended and its sequel were critically lambasted upon their release in 2014 and 2018, but the use of Skype and video chat technology was a fresh idea. Searching, though not a horror movie, was praised for its use of video chat footage in telling a twisty mystery story. Host, the first film to be shot entirely on Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic, has received critical praise for its ability to make use out of the current barrier to filmmaking. In this way, Host represents the decades-old DIY mentality of horror filmmakers, and proves that found footage horror movies aren’t necessarily dead. They just need to find a new, inspired outlet for resurrection.

Next: Host vs. Unfriended: Which Virtual Horror Movie Is Scarier (& Why)

Read more: screenrant.com

Recent Comments