In the 1920 s, Robert Moses designed a organisation of parkways smothering New York City. His intends, which included overpasses too low for public buses, have become an often-cited example of exclusionary blueprint and are argued by biographer Robert A. Caro to represent a purposeful barrier between the city’s Black and Puerto Rican residents and nearby beaches.

Regardless of the details of Moses’s parkway project, it’s a particularly memorable remembrance of the political strength of pattern and the ways that alternatives can exclude numerous groups based on abilities and resources. The growing interest in inclusive design highlights questions of who can participate, and in relation to the web, this has often represented a focus on accessibility and user experience, as well as on questions related to team diversity and governance.

But principles of all-inclusive blueprint should also play a role early in the specific characteristics and development process, during material modeling. Modeling defines what content objectives consist of and, by expansion, who will be able to create them. So if web professionals are interested in inclusion, we need to go beyond asking who can access content and also think about how the design of content can install barriers that make it difficult for some people to participate in initiation.

Currently, content simulations are primarily seen as reflects that indicate intrinsic designs in the world. But if the world is biased or exclusionary, this intends our content poses will be too. Instead, we need to approach content pose as an opportunity to filter out dangerous organizes and create methods in which more people can participate in stimulating the web. Content sits designed for inclusivity welcome a variety of enunciates and can eventually increase products’ diversity and reach.

Content poses as mirrors

Content modelings are tools for describing the objects that will make up a project, their facets, and the possible relations between them. A material mannequin for an art museum, for example, would typically describe , among other things, artists( including attributes such as name, nationality, and perhaps modes or academies ), and creators could then be associated with artworks, expoes, etc.( The content simulation would also likely include objects like blog posts, but in this article we’re interested in how we pose and represent objects that are “out there” in the real world, rather than content objects like articles and quizzes that live natively on websites and in apps .)

The common prudence when designing content representations is to go out and research the project’s subject domain by talking with subject matter experts and project stakeholders. As Mike Atherton and Carrie Hane describe the process in Designing Connected Content, talking with the people who know the most about a theme realm( like skill in the museum pattern above) helps to reveal an “inherent” structure, and detecting or divulging that organization ensures that your material is complete and comprehensible.

Additional research might go on to investigate how a project’s end users understand a province, but Atherton and Hane describe this stage as chiefly about terminology and detailed information. End users might use a different message than experts do or care less about the nuanced importances between Fauvism and neo-Expressionism, but eventually, everybody is talking about the same thing. A good material model is just a reflect that reflects such structures you find.

Fissures in the mirrors

The mirror approach works well in many cases, but there are times when the structures that subject matter professionals perceive as inherent are actually the products of biased structures that quietly exclude. Like machine learning algorithms trained on past school admittances or hiring decisions, existing designs tend to work for some people and evil others. Very than recreating these structures, material modelers should consider ways to improve them.

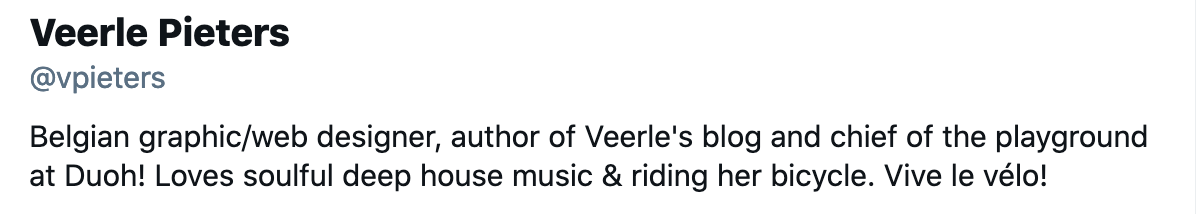

A basic instance is LinkedIn’s choice to require users to specify a company when creating a brand-new work experience. Modeling experience in this way is obvious to HR managers, recruiters, and most people who participate in conventional vocation moves, but it assumes that valuable know-how is only to be achieved by companionships, and could potentially discourage beings from registering other types of events that would allow them to represent alternative career moves and appearance their own stories.

Figure 1. LinkedIn’s current pattern for event includes Company as a required attribute.

Figure 1. LinkedIn’s current pattern for event includes Company as a required attribute.

These kinds of incongruities between required material attributes and people’s ordeals either procreate definite barricades( “I can’t participate because I don’t know how to fill in this field”) or increase the labor required to participate( “It’s not obvious what I should introduce now, so I’ll have to spend time thinking of a workaround” ).

Setting as optional subjects that might not apply to everyone is one inclusive answer, as is increasing the available options for responses compelling a collection. Nonetheless, while gender-inclusive selects provide an all-inclusive channel to handle form inputs, it’s also worth consideration when business objectives would be met just as well by providing open verse inputs that allow users to describe themselves in their own terms.

Instead of LinkedIn’s highly prescribed content, for example, Twitter bios’ lack of organization makes beings describe themselves in more inclusive rooms. Some people use the space to roster formal credentials, while others offer alternating forms of identification( e.g ., mother, cyclist, or coffee enthusiast) or jokes. Because the content is unstructured, there are fewer promises about its exploit, making pressure off those who don’t have formal credentials and demonstrating more flexibility to those who do.

Browsing the Twitter bios of decorators, for example, exposes a range of identification strategies, from lean credentials and affiliations to providing broad descriptions.

Figure 2. Veerle Pieters’s Twitter bio calls credentials, affiliations, and personal interests.

Figure 2. Veerle Pieters’s Twitter bio calls credentials, affiliations, and personal interests.

Figure 3. Jason Santa Maria’s Twitter bio squanders a wide-reaching description.

Figure 3. Jason Santa Maria’s Twitter bio squanders a wide-reaching description.

Figure 4. Erik Spiekermann’s Twitter bio expends a single word.

Figure 4. Erik Spiekermann’s Twitter bio expends a single word.

In addition to considering where structured content might omit, content modelers was necessary to consider how length specifications can implicitly originate impediments for content founders. In the following discussion, we look at a project in which we chose to reduce the length of contributor bios as a practice to ensure that our material mannequin didn’t leave anyone out.

Live in America

Live in America is a performing arts festival scheduled to take place in October 2021 in Bentonville, Arkansas. The objective of the project is to survey the diversity of live performance from across the United Position, the territory of the state, and Mexico, and bring together groups of creators that represent distinct local habits. Radicals of performers will come from Alabama, Las Vegas, Detroit, and the border city of El Paso-Juarez. Indigineous performers from Albuquerque are scheduled to put on a faggot powwow. Musicians from Puerto Rico will plan a cabaret.

An important part of the festival’s mission is that many of the performers involved aren’t integrated into the world of large-scale art conservatories, with their substantial fiscal resources and social ties. Undoubtedly, the project’s purpose is to locate and showcase examples of live performance that fly under curators’ radars and that, as a result of their lack of exposure, divulge what performs different communities truly unique.

As we began to think about content pose for the festival’s website, these goals had two immediate outcomes 😛 TAGEND

First, the idea of exploring the subject domain of live performance doesn’t accurately work for this project because the experts we might have approached would have told us about a copy of the performing arts world-wide that commemoration organizers were solely trying to avoid. Experts’ mental prototypes of performers, for example, might include attributes like residencies, fellowships and subsidies, program vitae and awardings, artist statements and long, detailed bios. All of these attributes might be perceived as inherent or natural within one, homogenous community–but outside that parish they’re not only a ratify of misalignment, they represent an obstacle to participation.

Second, the purposeful diversity of fair members means that locating a shared mental simulate wasn’t the goal. Festival organizers want to preserve the diversity of the communities involved , not producing them all together or show how they’re the same. It’s important that people in Las Vegas think about concert differently than parties in Alabama and that they organize their projects and whole relationship in different methods.

Content modeling for Live in America involved defining what a community is, what research projects is, and how these are related. But one of the most interesting challenges we faced was how to sit a person–what properties would stand in for the people that would make the episode possible.

It was important that we pattern participants in a way that preserved and foreground diversification and also in a way that included everyone–that tell everyone take part in their own way and that didn’t overburden some people or ask them to experience undue anxiety or act added work to originate themselves fit within a pose of recital that didn’t match their own.

Designing an all-inclusive material model for Live in America meant believe hard-bitten about what a bio would look like. Some players come from the institutionalized art world, where bios are lengthy and detailed and often engage in intricate and esoteric forms of credentialing. Other members create art but don’t have the same reserves. Others are just people who were chosen to speak for and about their communities: columnists, chefs, professors, and musicians.

The point of the project is to highlight both operation that has not been recognized and the people who have not been recognized for realise it. Requesting for a written information that has historically been built around institutional recognition was able to highlight the hierarchies that commemoration organizers want to leave behind.

The first time we brought up the idea of limiting bios to five names, our immediate response was, “Can we get away with that? ” Would some creators balk at not being allowed the seat to list their honors? It’s a ridiculously simple intuition, but it also gets at the heart of content modeling: what are the things and how do we describe them? What are the formats and limitations that we put on the content that would be submitted to us? What are we expecting of the people who will write the content? How can we configure the rules so that everyone can participate?

Five-word bios place everyone on the same ground. They invite everyone to create something new but also feasible. They’re analogous. They placed well-known artists next to small-town poets, and tell them play together. They let in diverse words, but keep out the historical structures that rectified parties apart. They’re also recreation 😛 TAGEND

Byron F. Aspaas of Albuquerque is “Dine. Tachii’nii nishli Todichii’nii bashishchiin.”Danny R.W. Baskin of Northwest Arkansas is “Baroque AF but eating well.”Brandi Dobney of New Orleans is “Small boobs, large-scale dreams.”Imani Mixon of Detroit is “best dresser, dream catcher, storyteller.”Erika P. Rodriguez of Puerto Rico is “Anti-Colonialist Photographer. Caribena. Ice Cream.”David Dorado Romo of El Paso-Juarez is “Fonterizo historian wordsmith saxophonist glossolalian.”Mikayla Whitmore of Las Vegas is “hold the mayo, thank you.”Mary Zeno of Alabama is “a down home folk poet.”

Modeling for inclusion

We tend to think of all-inclusive design in terms of removing barriers to access, but content modeling also has an important role to play in ensuring that the web is a place where there are fewer barriers to creating content, particularly for beings with diverse and underrepresented backgrounds. This might involve rethinking the use of structured content or asking how length specifications might establish burdens for some people. But regardless of the tactics, designing inclusive content modelings begins by acknowledging the political operate that these patterns perform and requesting whom they include or exclude from participation.

All modeling is, after all, the creation of a world. Modelers build what things exist and how they relate to each other. They start some things hopeless and others so difficult that they might as well be. They let some people in and impede others out. Like overpasses that avoid public bus from reaching the beach, exclusionary representations can calmly determine the landscape of the web, exasperating the existing lack of diversification and drawing it harder for those who are already underrepresented to gain entry.

As discussions of all-inclusive intend continue to gain momentum, material modeling should play a role accurately because of the world-building that is core to the process. If we’re building world-wides, we should build worlds that allow in as numerous people as is practicable. To do this, our discussions of content modeling need to include an expanded range of analogies that are beyond precisely mirroring what we find in the world. We should also, when needed, filter out formations that impact negatively or exclusionary. We is generating openings that ask the same of everyone and that use the generativity of everyone’s responses to create web makes that develop out of more diverse voices.

Read more: alistapart.com

Recent Comments